Location 1998

Fermoy Gallery, King's Lynn Arts Centre in collaboration with King's Lynn Museums

Location focused on contemporary debate considering the relationship between visual research and creative processes. (Patrizio & Theophilus, 1998, p.3)1. The exhibition commissioned new works by myself and textile artist Polly Binns, with the resulting exhibition revealing the resonance between disparate practices and the role of shared research principles in the construction of meaning. The collaborative nature of the project showcased new work initiated through sustained research into two very different aspects of the Norfolk environment.

The exhibition resulted from full access to the Lynn Museum's unique collection of drawings by the artist and explorer Thomas Baines. Born and raised in Kings Lynn, Baines became known for his travels in Southern Africa during the mid nineteenth century. He is well known as one of a pool of European artists recording Africa during the Victorian period and his works and journals are in a number of major African collections although very little of his work remains in the U.K. Baines' response to the vast continent before him was at times predictable, at times idiosyncratic. As the biographers have observed, 'It is not Africa that Baines describes but his own British response to it.'2 Most notably he accompanied David Livingstone on the Zambezi expedition between 1858-59.

Baines’ real interest was in recording life around him and he sketched incessantly to provide raw material for larger painted works. His paintings are predominantly propagandist and melodramatic with a tendency to rearrange fact in favour of British Imperialist ideals. However his documentary sketches are a more honest record of what he saw and from the outset and are engaging in their spontaneous composition, representation and technique.

The work produced in response to Baines’ sketches drew upon aspects of gaze theory, as described by Andrew Patrizio in the accompanying catalogue

Chubb’s preoccupation with the relationship between looking and seeing (which she shares very much with Binns) then led her to concentrate on heads of human figures, in around 36 of the drawings. The theme became those things that are the object of another’s gaze. For example, tribes people and colonials in combat; or quieter, domestic scenes where Africans are depicted under the dignified social gaze of each other; Baines himself as artist-observer. Equally in the wider context, the gaze dominates in the process of curatorial perusal of the drawings as they were accessioned into the Lynn collection; or with these works’ ‘rediscovery’ under the eyes of a contemporary artist, Chubb; and ultimately, of course their scrutiny as they are exhibited for us today. (1996, p.10) 3

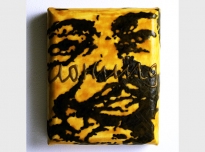

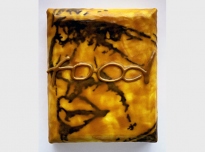

Each Baines drawing was scanned and manipulated to fit a stretcher the same size as the original work. The enlargement of detail revealed the gestural immediacy of the drawings – some remained recognisably figurative whilst others became more abstract.4 Words taken from the catalogue details of the drawings were superimposed over the images with the original handwriting enlarged and representing another stage of looking. The words describe much more than the visual content of the drawings and are relevant to both the original scene and encounter as Baines drew, whilst equally describing ongoing actions, facts and emotions.

The paintings were shown in a compact group that mirrored the arrangement of the original drawings shown alongside them. The museum context is pivotal to an understanding of the work. As Andrew Patrizio summarises:

Chubb’s work suggestively asks us to draw conclusions between the chosen subjects of Thomas Baines, the taxonomic activity of the cataloguer, and our own subjectivity. The connecting eye is used as a political and analytical tool. The complex relationship between the real life experience of a nineteenth-century explorer, its manifestation through museum artifacts, and its re-evaluation through Location, is made explicit by Chubb in the decision to display, adjacent to her final series of panels, the original drawings. The translation of these historical artifacts into a digital medium – the same means by which we are bombarded by media images from Africa and elsewhere – indicates, for the artist, the continued contemporary relevance and yet difficulty of global exchange. (1996, p.12).5

1 Patrizio, A., Theophilus, L. (1998) Location: Polly Binns and Shirley Chubb King’s Lynn Arts Centre

2 Carruthers, J. & Arnold. M (1996) The Life and Work of Thomas Baines Fernwood Press

3 Patrizio, A., Theophilus, L. (1998) Location: Polly Binns and Shirley Chubb King’s Lynn Arts Centre

4 It became apparent that some images now resembled the landscape source material of Polly Binns’ work, with Baines drawings retaining the emptiness and economy of the Norfolk landscape.

5 Ibid

Text © Shirley Chubb, 2011